Portal 2 (PC) retrospective

There was a time, way back in 2007, when Valve was a company that made video games, and released a little collection called The Orange Box. Having already completed Half-Life 2 on PC by that point, I had the most fun with a new title tacked onto the end of the compendium named Portal, which presented a unique blend of the first-person shooter and puzzle genres.

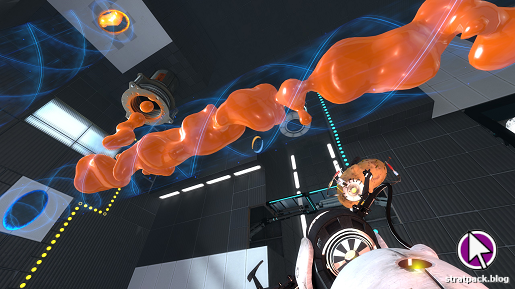

For the uninitiated, Portal tasks the player with solving various challenges using a portal gun. This tool can fire two portals – orange and blue – which appear as large ovals on the walls. Walk through one and you’ll come out of the other, and the same holds true for various objects you’ll use to complete the levels. This innovative gameplay mechanic, plus some sarcastic, fourth wall-breaking dialogue, earnt Portal a place in many gamers’ hearts.

In 2011, Valve published Portal 2, which made many of the era’s “best of” lists, but for one reason or another never joined my game library. Curious, I picked up a copy for the grand sum of £1.43 in a recent Steam sale, in the hope that it still stands up 11 years later. After an eight-hour playthrough of the sequel, I can say that Portal 2 tries to do much more than the original, and while it is successful in some respects, in my view it fails in others.

Thinking with portals

Portal 2 begins with the player waking up in a room at Aperture Laboratories, and it doesn’t take long for its signature tone to show as we’re instructed to complete our mandatory time staring at a painting on the wall to feel “mentally reinvigorated”. With that complete, we go back to bed, but apparently we sleep for too long because when we wake the dormitory building is ruined and there’s someone pounding on the door.

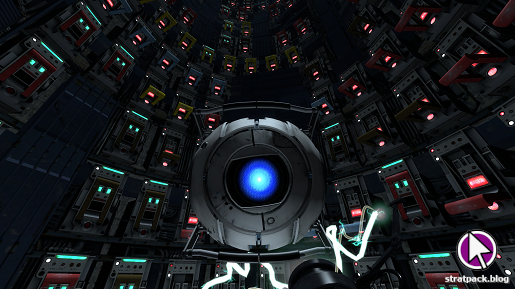

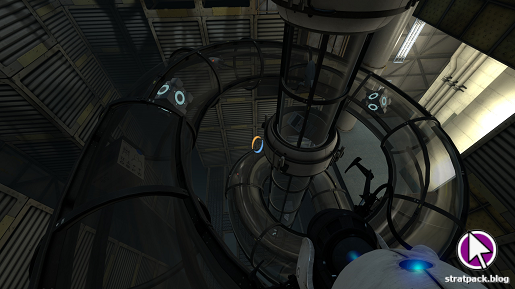

This turns out to be Wheatley, a hapless but well-intentioned floating eye robot voiced by Stephen Merchant. There’s a clever bit here where the game asks us to press A to speak, but that button just makes us jump, which Wheatley points out. Now we’ve familiarised ourselves with the controls and met our new companion, Wheatley rips our bedroom from the building and whisks us off to the main facility for some “emergency testing”.

At the test lab, we start working with portals. As in the first Portal game, each puzzle is essentially a self-enclosed cell with an entry and an exit, beyond which there is a lift to reset everything and take us to the next level. Between the player and their escape can lie any combination of:

• Weighted cubes - usually need to be placed on buttons

• Light-refracting cubes - can be used to divert lasers to receptors

• Lasers - deal damage, but activate devices when pointed the right way

• Turrets - monitor for the player and kill them near-instantly on firing

• Gravity rays - push and pull objects, including the player

• Various gels and gel dispensers

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves a little here. The first puzzles are relatively simple – initially we’re only allowed to use portals provided to us, and then eventually we’re allowed to fire blue portals. This introductory section was obviously required to bring new players up to speed with the series’ mechanics, but it won’t be too challenging to anyone who played the first game. Portal 2 wants to do more than this, however…

Dude, where’s my cake?

Valve had something of a problem coming into Portal 2. The standout character of the original Portal was GLaDOS – the robotic, yet sassy host putting us through all these tests. But we killed her at the end of the game. So to ensure she could return and deliver more of the wisecracks we all love, they contrived a way for the clumsy Wheatley to accidentally flip all her switches, bringing her back to life. She takes us to the heart of the test centre, we get the orange portal gun, and the real fun begins.

GLaDOS says she wants to test with us forever, but she’s obviously still harbouring some resentment about the whole killing her thing. “Well done,” she says after another completed puzzle. “Here are the test results: You are a horrible person. We weren’t even testing for that.” Wheatley pops in from time to time, telling us he’s working on a way to break us out.

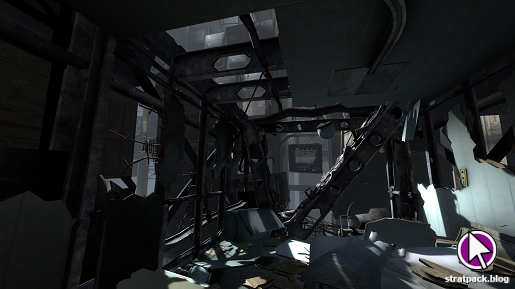

Eventually, he sets us free through a hatch in the test chamber wall, and we’re dashing through the service passages of the testing facility past production lines manufacturing cubes and turrets, on the run from GLaDOS. It’s neat to use portals in a non-testing environment, although it does come with some difficulties, which I’ll discuss in more detail later.

It’s all very fast-paced, but this is where Wheatley started to grate on me a bit. I like Stephen Merchant, and have enjoyed some of his other work – especially his role as Ricky Gervais’s agent in Extras – but Wheatley just does not stop providing irritating commentary on everything that we do, and it becomes especially annoying when he starts nagging you to get a move on when you’re trying to figure out what the game wants you to do to move to the next area. Admittedly there are some funny jokes in there, but compared to GLaDOS’s cold delivery it’s all a bit overdone and obnoxious.

Anyway, GLaDOS captures us in a cell, but she uses some faulty turrets we and Wheatley produced, which break the glass. Wheatley shows up and we plug him in and transfer his consciousness into GLaDOS’s body to end her reign over the testing centre. But somewhat predictably, Wheatley is less keen to escape once he realises his newfound power. Instead, he condemns GLaDOS to life inside a potato battery and becomes evermore suspicious of us, eventually punting us both down to the pits of the facility.

Learning from the past

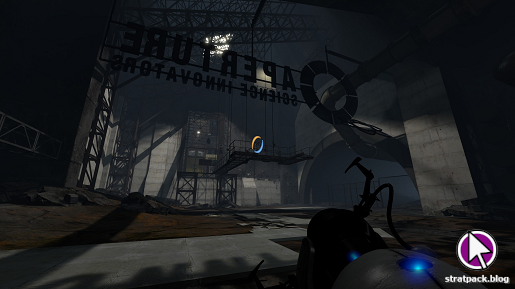

What follows is probably the best segment of the game in terms of both story and gameplay. We end up in a decrepit Aperture testing facility, which has a BioShock-esque vibe with its decaying mid-century furnishings. The voice guiding us through this area is that of Cave Johnson, the founder of Aperture Science. Since he’s dead and can’t be there in person, we are played recordings he prepared for candidates as they reached each test chamber, which feels more akin to the dialogue in the original Portal.

The puzzles are more challenging here, and while they do make use of old-fashioned versions of the modern testing equipment, the historic test centre also has its own tricks up its sleeve. These tricks, it turns out, come mostly in the form of the aforementioned gels and dispensers:

• Blue gel – lets you bounce higher to reach new areas

• Orange gel – lets you sprint at super speed and build momentum

• White gel – moon rock-based (remember that), makes surfaces portalable

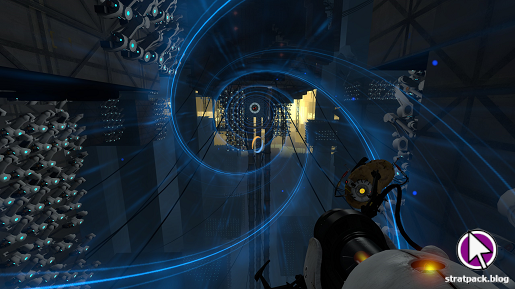

These are used in conjunction with each other to create some great puzzles that really freshen up the formula. By the end of this segment you’ll be placing portals under dispensers to distribute gel where it’s needed before executing elaborate combinations of sprints, jumps, bounces, and portal shots to reach your destination. The most satisfying parts of Portal are those that make you feel super smart for thinking in more than three dimensions to solve a chamber, and these puzzles certainly deliver.

We eventually find GLaDOS in her potato form and begin to make our way through the 70s-era areas, and then those from the 1980s. Along the way we’re met with the “startling” revelation (it’s actually signposted as much, if not more than, Wheatley’s turn to the dark side) that GLaDOS is actually the digitised form of Johnson’s personal assistant Caroline, who was put in charge of the facility when he died. GLaDOS has a vague recollection of this, which serves as her motivation to kill Wheatley and regain control.

Taking back control

Forming an unlikely partnership, we fight our way to the surface to deal with Wheatley. We find that he’s already making his mark on the test centre, and has apparently been crossbreeding cubes and turrets to produce limping, non-functional offspring. When he learns of our presence he wants to test us, but his chambers are far too easy, so he steals GLaDOS’s designs. This is where the gravity beams come into play, again adding a challenging twist as we now need to try to direct objects – and ourselves – through the air. As the thrill of watching us test wears off, Wheatley grows slowly more insane.

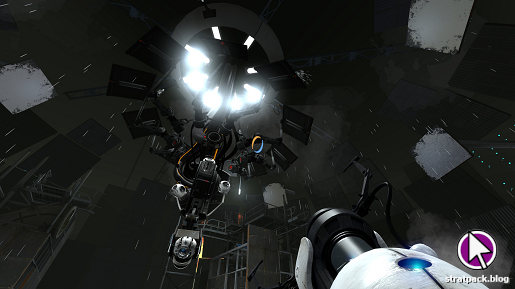

For once in a game with an unusual central mechanic, the final boss fight is actually very well done. Wheatley floats around in the middle of the arena and fires missiles at you, which you must send through portals at various angles to circumvent his shields and hit him. GLaDOS throws corrupted cores to you at various intervals, which you attach to Wheatley to gradually weaken him. Once enough of these are connected, we’re directed to press the same “stalemate button” we used to defeat GLaDOS earlier.

Here’s the game’s final masterstroke. Wheatley has rigged the button to explode, which damages the testing centre and blows a hole in the roof. There it is, staring right at you: the moon. You remember that the white gel that made surfaces portalable was made of moon rocks, and take a chance. You fire a portal directly at the moon, and the vacuum of space tears Wheatley apart. It’s rare that a game’s final moments are my favourite, but this was a great callback and ups the stakes while so well while maintaining mechanical consistency that it may be the exception to the rule.

GLaDOS, now in control, pulls us back through the portal as Wheatley spirals off into space. Back on Earth, she decides that the least problematic option is just to let us go. We ascend to the surface past a bizarre choir of dancing turrets (I have no idea how that idea got any further than the brainstorming whiteboard) and step outside into the sunlight. The end credits are set to another song – this time sung by GLaDOS – about how happy she is to finally be rid of us, and we get a final scene of Wheatley drifting through space expressing his remorse before everything fades to black.

Straying from the formula

There were parts of Portal 2 I loved, and elements I didn’t see the need for at all. Despite its first-person perspective, Portal is a puzzle game, and it works best when it’s challenging the player to use the tools at their disposal to escape the cell the testing centre has built for them. There’s something immensely satisfying about the Checkoff’s gun-ness of it all – you know everything there must be used, but how? At the game’s strongest it follows an enhanced version of this format, and you’re forced to think not just in portals but also according to the effects of gels and gravity rays.

But in trying to make Portal 2 bigger and better than its predecessor, Valve had to break it out of that bright white box. Beyond the testing chamber, it’s unclear what’s part of the puzzle and what’s just scenery. The most jarring moments were when the game seemed to be guiding me down a path, only for me to realise after much retreading that it was expecting me to have shot a portal at a tiny grey dot a mile away in the previous area.

Portal 2 is often brought up in “game of the generation” conversations, but honestly I prefer the far more concise and focused original. That said, there are still plenty of enjoyable puzzles in the various testing centres you explore over its eight-hour span, and even if Wheatley gets quite annoying early on, there is a lot of content that subverts the player’s expectations in amusing and surprising ways. If you didn’t play Portal 2 back in 2011 then by all means go back for a playthrough – just don’t expect the earth-shattering experience some talk it up to be, and don’t overlook the original.