BioShock Infinite (PC) retrospective

I’m on the war path in 2022, finally playing through all sorts of games that I probably should have completed years ago, but for one reason or another passed me by. Next in line is BioShock Infinite - the 2013 follow-up to two fantastic games that I hold among my all-time favourites. The switch from my beloved Rapture to Columbia demoted this one to my “to play” list, and once the initial hype died down so did any urgency I had to pick it up - until, that is, it went free on the Epic Games store a few weeks ago.

BioShock Infinite is a game that can certainly be described as interesting on several levels. The core premise and story itself is interesting, including how it entwines itself with the series’ universe. The potential readings into what the designers and writers meant by it all are interesting. And at its most fundamental level, as a piece of video gaming entertainment, it’s interesting to notice the ways in which the BioShock formula has been tweaked to paper over some of the shortcomings and criticism of the first two games.

A tale of two timelines

The most fundamental difference between BioShock Infinite and the two games that came before it is that the iconic underwater city of Rapture is no more. This time out, our setting is Columbia – a flying city of interconnecting platforms that was established by Father Comstock, a religious leader who is seen as the ultimate authority and God’s right-hand man. The brief opening sees you take a row boat to a lighthouse, and essentially only fills you in that you’re a man named Booker DeWitt who has travelled from New York to settle his gambling debts. Then it launches you into the clouds.

The parts of Columbia you are shown carefully construct your impression of the city over the first hour or two. Unlike Rapture, the city is thriving when you arrive, and it initially seems rather idyllic until you begin to notice certain undercurrents. These eventually come to the surface when DeWitt wins a raffle, the prize for which is presented by “the loveliest white girl in Columbia”. Your reward, it turns out, is a chance to hurl a ball at a pair of lower-class citizens in stocks, but before you can do anything DeWitt is recognised as the “false shepherd”. From that moment, you’re on the run.

A switch is flicked here, and the game becomes a lot more violent both literally and figuratively. The shooting begins and the racism bubbles to the surface as your travels take you through areas branded with slogans like “Protecting our Race”. I was a bit worried at this point that the sum of the game’s story would be a lazy “religion is bad and racist”, but Infinite has more up its sleeve yet. Things get properly interesting when we run across Elizabeth – the girl DeWitt’s debtors have apparently been demanding.

Held captive and under observation by Comstock, Elizabeth is quickly established as having a supernatural power to open “tears” to other worlds. We break her out of her tower and – after some convincing that killing so many people is a necessity that doesn’t make us evil – she joins us in a failed escape attempt. We’re knocked out, and when we wake up we’re introduced to the Vox Populi – a rebel group attempting to start an uprising and overthrow Comstock. They’ll help us if we provide weapons.

Elizabeth is enamoured with the Vox and their promise of a better and fairer life for the people of Columbia, but when she brings us into a world where their revolution is in full throw it is clear that they are bent on tearing the city apart and killing even the most insignificant citizens. In this timeline DeWitt is their martyr, and the Vox turn on us because a living Booker “complicates the narrative”. Even Elizabeth steps in when the Vox leader Daisy is about to kill an industrialist’s child, and stabs her in the back.

A face-off with the spirit of Lady Comstock yields a twist – until now we’ve been led to believe that Elizabeth is Comstock’s daughter, but this is thrown into doubt. When Songbird – a giant, mechanical brute of a bird that guarded her tower – tracks us down, she sacrifices herself into captivity to save DeWitt’s life. Another jump between worlds leads us into a mental asylum, where we see glimpses of Elizabeth’s “rehabilitation” by Comstock’s regime, and a further switch enables a brief conversation with an elderly Elizabeth in 1984, set against the backdrop of Columbia invading New York. She hands us what will later turn out to be the key to stopping Songbird.

A lot happens from here on out as the game culminates in a fight through Comstock’s airship to kill the man himself. We have a final (and long) battle with the Vox on the top deck, using the new intel to harness Songbird to our advantage before we lose control of him and Elizabeth is forced to transfer us into another world… and we end up in Rapture. It turns out Columbia and Rapture exist in parallel worlds. When we surface, there are lighthouses as far as the eye can see, and Elizabeth explains that there is “always a man, always a city” - an infinite number of alternate timelines.

We learn a lot through some muddled scenes here, but the overall gist is this: Elizabeth is DeWitt’s daughter Anna, who he was forced to hand over to Comstock to settle his gambling debts. Comstock himself was rendered impotent due to inter-world travel via tears, but wanted Elizabeth to be his heiress and take over Columbia when he stepped down or died. Hearing this, DeWitt wants to go back in time and kill Comstock so none of this can happen, but realises that Comstock is in fact another version of himself.

DeWitt was offered a chance to be baptised and absolved of his sins when he returned from war, but turned the priest down. In a parallel timeline, he accepted the baptism and became religious, eventually transforming into Father Comstock and founding Columbia. As Elizabeths from various worlds converge on DeWitt in the lake where this took place, he allows them to drown him to keep her from the harm that would otherwise be inflicted by Comstock. The screen fades to black, and the game ends.

Reading between the lines

At a high level, BioShock Infinite can be read as a warning about extremism on both sides of politics. Father Comstock’s regime is authoritarian, with slogans on the billboards, police in military uniforms on the street corners, and a horribly mistreated underclass of workers and ethnic minorities. But when the Vox Populi rise up, they too commit atrocities, with indiscriminate killings of anybody they deem to be part of the establishment – even children. It’s a cautionary tale about how easy it is for anyone to convince themselves they are “the good guys” and justified in undertaking horrible acts because they think their cause is worthy enough.

This is supported by a few segments that offer commentary on the gulf that sometimes exists between the stories we tell ourselves and reality. Notably, Elizabeth is thoroughly convinced by just a few lines from the Vox Populi about how they’ll make Columbia a better place. Later, we see the priority the revolutionary group places on the narrative it has built. Although he is also fighting against Comstock, a dead DeWitt is more useful to Daisy Fitzroy because if he is living then he loses his martyr status, which is a cornerstone of their propaganda. Building a polarising story is more important to them than their integrity. Infinite shows the power of blind adherence to ideology to corrupt, even when a movement started with worthy intentions.

It’s an important and relevant message for the real world, but it doesn’t quite work in-game because Comstock’s regime is so cartoonishly evil that you could make an argument that just about anything else would have been preferable. In fact, everyone in BioShock Infinite is a hopeless caricature – Comstock as the insane cult leader and industrial tycoon Albert Fink as the capitalist without morals, for example. Daisy herself is a rare example of a character with some ambiguity – initially seeking justice before power pushes her over the ethical edge – far more interesting than all-out good or evil.

It’s worth noting here that all this is conveyed in a much more engaging way than the themes of the first two BioShock titles. This is possible because Columbia is alive around us, and there are NPCs we can listen to and interact with who aren’t just manic splicers rambling nonsense – ranging from major characters like Comstock and Daisy Fitzroy to enemies and random citizens. In BioShock, most exposition came though audio logs dotted around the ruins of Rapture. They still exist in Infinite and supplement the story with some colour, but the bulk of the main narrative is absorbed through experience – conversations with characters and observation of the city in motion.

There are also points, especially early on, where Elizabeth expresses her dismay at DeWitt’s killing. This is a theme more akin to that of the original BioShock, which questioned gamers’ ability to make their own decisions. This is a first-person shooter, and we simply accept that shoot is what we must do in every situation where the game will let us. Elizabeth, on the other hand, is new to this world, and shocked at the carnage we leave in our wake. It’s not explored as consistently as it could have been, but this thread at least comes to a head when she turns to violence herself later on, stabbing Daisy in the back to spare the young boy she’s about to kill.

To take this a step further, Elizabeth and her character development could also be read as an analogy for the naivety of youth in general. She leaves captivity having read about the world in her library (akin to school) and is shocked at the reality outside. Her idealistic pacifism is eventually shattered, as I mentioned above. And she is impressionable enough to be won over quickly and completely by the Vox Populi’s promises, only realising her mistake when she sees what their revolution really looks like. The course of Infinite’s story is an education in practicality and critical thinking for her.

Playing the game

While the BioShock series lends itself to discussions of story and themes, gaming is an interactive medium, and ultimately none of it would stand up if the gameplay experience was no good. What we get with BioShock Infinite is a steady refinement of what came before in the first two games. The series’ shooting has never been the best. Unlike something responsive and weighty like Call of Duty, combat in this game is a lot more about wearing down enemies’ health bars over time using the tools at your disposal.

And those tools are as varied as any game’s. The selection of guns is what you’d expect from a modern FPS, but the “vigors” – powers embedded in your hand which replace plasmids this time around - are where the designers really got creative. These range from classics like lightning and fire to some that are really out there. My favourite was Murder of Crows, which allows you to throw a nest at your enemies’ feet so that birds attack them. Vigors are what sets BioShock apart, and my only complaint is that the game didn’t make it clearer that while two vigors sit in your quick-use slots for easy access, you can still access them all at any time via a radial menu.

Elizabeth is unique as a companion. While most sidekicks are annoying at best and game over machines at worst, Elizabeth is invulnerable to damage and serves instead as a tool to enhance the player’s experience. She picks locks to helps you progress, and often runs ahead, helping to guide you in the right direction. She throws items like ammo and money to Booker, and even her tears become a gameplay mechanic – you can shout to her to fabricate cover, weapons, health, turrets, and more. It’s so rare for a companion to be so genuinely useful that I found this directly contributed to the weight of the story, and you miss her when she’s taken away.

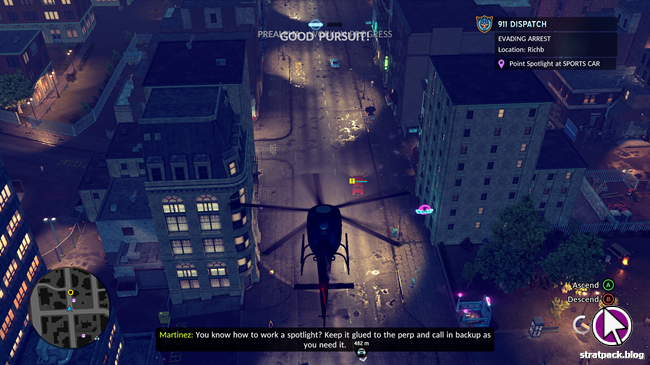

Columbia itself also offers a chance for Irrational Games to add some variety to the series’ gameplay. Gone are the claustrophobic corridors of Rapture, which have been replaced in large part by open outdoor areas. The difference is night and day, and you’re much more likely to be engaged in ranged combat than in even the most expansive parts of Andrew Ryan’s underwater city. Staying on brand as a flying city, Columbia is full of Sky-Line rails, which enable DeWitt to slide around on a grappling hook-style device and drop down on enemies from above when the opportunity arises.

Foes range from standard foot soldiers (melee, pistol, machine gun, RPG, sniper, etc.) to specialists. Firemen blast you with flames, and raven-themed warriors can teleport and hack at you with a sword, for example. The largest and most challenging enemy type is the Handyman, which benefits from great speed, extended reach, and the ability to take a large amount of your health if it hits you. The best of the lot, however, was the Motorised Patriot – robots modelled after the US Founding Fathers who storm into battle in a hail of bullets, shouting patriotic slogans as they join the fray.

Some of Infinite’s most memorable sequences are when the game decides to mix things up. Lady Comstock provides one of the more interesting fights, summoning ghost soldiers to do her bidding in a way that reminded me of Clifford Unger in Death Stranding. I thought the battle was fairly short at first, but she returns several times in different arenas. Mechanically, it’s a nice change of pace to be forced to balance fighting the boss herself with dealing with her henchmen as they advance on your position.

Another notable mention goes to the mental asylum where Elizabeth is held later in the game. This features surprisingly good stealth gameplay, where if you are caught by a rotating sentry’s torch you are ambushed by a group of tough inmate enemies in creepy masks. The section culminates in a huge jump scare, where you pull a lever and turn around to find one of the sentries, which you’ve been tiptoeing around all along, right behind you.

Final thoughts

I have no regrets about taking the time to play BioShock Infinite after nine years. There were elements I enjoyed – the opening chapel, the Motorised Patriots, and some of the grander spaces will all stick with me – but I felt Columbia was less atmospheric than Rapture, held back by the little details. The vending machines, for example, were just as creepy as Rapture’s, but their voices felt like imitations of the old ones (which can be explained by the parallel worlds plot point, but still). Maybe it’s also because I missed Rapture’s claustrophobia and the horror elements that the first two games employed, but it also seemed like the sub-nautical state had more of a story to tell as a city, while Infinite’s tale was much more about the individuals.

If that sounds like I’m being negative, I’m not. Infinite was still a fantastic game, head and shoulders above most other titles out there – particularly in the FPS genre – and it was clear that Irrational Games had spent a lot of time working out how they could act on some of the criticism directed at the first two games in the trilogy while still maintaining its character. While the transition to a new city was a mixed success, the gameplay is a definite step up, especially with Elizabeth and her tears to keep you company.

There aren’t many games with enough depth to be worth a 2,500-word retrospective, but BioShock has pulled it off again. BioShock Infinite is a mesh of complex ideas, some of which work better than others, but the underlying message about the perils of blind adherence to ideologies on all sides of the political spectrum is if anything more relevant now than it was back in 2013. If politics and philosophy aren’t your thing, there’s also a compelling personal story about DeWitt, Comstock, and Elizabeth to unpick. And if you don’t care about that… Well, there’s quite an enjoyable video game here, too.