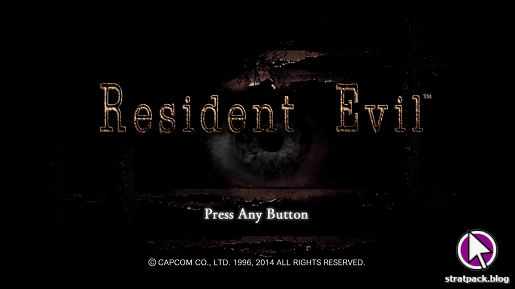

Resident Evil HD Remaster (PS4) retrospective

Everyone has a series or two that are widely regarded as the pinnacle of video games that they’ve never got around to playing. For me, Resident Evil is one of them. The first game in the series, which now spans nine core titles and numerous spin-offs and remakes, was released on the PlayStation in 1996. I have a vague recollection of playing a snippet on an old demo disc, but other than that I’d somehow avoided playing it for 26 years.

Even after I’d decided to pick up 2015’s Resident Evil HD Remaster on PS4, I had my apprehensions. Certain games have a “you had to be there” quality to them - I bounced off the old Pokemon games when I tried to play them in recent years, for example. Even with retouched graphics and controls, would the base game still stand up in 2022 for someone without the nostalgia Capcom were likely banking on with this release? It was time to find out.

Setting the scene

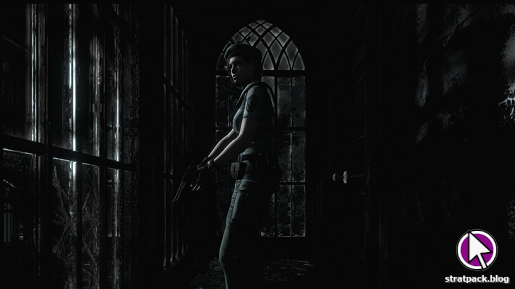

Resident Evil dumps you straight into the thick of the action. You can choose to play as either Chris Redfield or Jill Valentine (I chose the latter, and later learnt they have unique perks), members of the elite S.T.A.R.S. team, who are investigating the disappearance of their sister squad amidst a growing spate of murders in Raccoon City. When they are attacked by a pack of demonic dogs they are chased to a mansion, where they seek refuge.

The game pleasingly coheres with the dramatic principle of unity of place, as you spend its entirety exploring the mansion, finding missing members of your team, and uncovering the dark secrets it holds regarding the T-Virus and the Umbrella Corporation. The set-up is simple and the twists are all flagged well in advance, but the execution is strong enough that it’s still gripping, and by the end of the game you’ll know the map like the back of your hand.

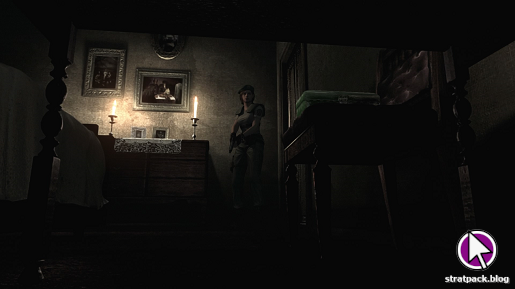

The mansion is split into rooms, which function as cells much like the areas in earlier Metal Gear Solid titles. The camera is static, changing between angles when the player character reaches the edge of the screen. This has the benefit of allowing for some beautifully detailed static backgrounds, but the revamped controls aren’t suited to it. When the camera changes, so does the direction you need to run, and you can end up spinning in circles if you don’t adjust quickly enough - frustrating at the best of times, but especially awful when you’re running from an enemy and it hinders your escape.

It’s also something of a mixed bag when it comes to how the game uses the camera. Sometimes it rewards close attention, showing a zombie around a 90-degree corner with a conveniently placed mirror to give you a heads up. Other times it’s not so kind, and a particularly annoying recurrence was areas that forced me to run directly into the camera, only for a zombie to be hidden right behind it ready to pounce before I had a chance to react.

A horror-themed puzzle box

I started Resident Evil expecting survival horror, but quickly discovered that the bulk of the game was actually more puzzle-based. You spend your time exploring the mansion, memorising routes, and passing trials to win keys. You’ll be traversing the map time and again as you solve challenges and unlock new rooms, and discovering what’s behind a previously locked door is a treat - enemies are usually just an inconvenience along the way.

The puzzles themselves are usually about deciding which objects go together in which order and knowing where to use them. They’re challenging enough to make you think, but follow a coherent enough course of logic that they’re not so difficult you’ll be stuck for ages wondering what to do. Some involve some basic memorisation or mental maths, and my notes for this article were interspersed with jotted-down codes, numbers, and colours.

While the puzzles and use of the map are cool, the inventory management system is not. You have limited slots and can only swap items out in storage boxes in safe rooms. This means you need to keep as much space open as possible for new items, and if you realise you need a previous item for a puzzle you’ll have to trudge back through the zombie-filled corridors for it. This makes trial and error expensive - especially with limited ammo.

Facing your fears

While the puzzles are the stars, the enemies add the colour. Over the game’s 11-hour span you’ll encounter various types of zombies, dogs, snakes, plants, crows, bees, and more. They’re all quite intimidating, especially given the stakes the save system introduces, but entering a room to see a giant spider right above my head - seemingly rendered in more detail than anything else in the game - is certainly a moment that lingers in the memory.

The zombies themselves have fairly basic AI. They’ll move towards you at various speeds, then either grab or swipe at you, and mainly serve to keep you on your toes while you’re darting to and from puzzle points. They don’t generally move between rooms, but they do persist in rooms you leave them in, so you’ll be taking mental notes of which areas to stay well away from. On rare occasions a zombie will burst through a door or window into the room you’re in, and it happens so intermittently that it’s always a shock.

Shooting takes some getting used to. Your character has an auto lock-on, but sometimes they don’t face the way they’re aiming so lining your shot up can still be tricky. There’s some randomisation at play, meaning the same type of enemy can take different numbers of shots to kill, and zombies have such long death animations that it can be difficult to tell when they’re finished, making it easy to waste ammo in a game where it’s already sparse.

You’ll soon learn that it’s best to avoid fights with random zombies where possible. The bosses are memorable and intense enough to get the heart racing, ranging from an even bigger spider to gigantuan snakes. Jill’s health is relatively weak and even a regular enemy can normally kill you in a few hits, but the challenge tends to dissapate once you nail a run-and-gun technique - by modern standards, you’re mostly fighting the camera and controls.

PS1-era quirks

I really enjoyed the additional details you can learn by interacting with items. These one-line notes can help to build suspense - for example, when a rope looks “recently cut” or firewood looks “fresh” and you know someone is close by - or can provide hints when examining puzzle-related objects. There are also a few diaries dotted around that tell some quite heartbreaking stories of the subjects and scientists contending with the T-Virus.

Another cool feature - especially for a game of this age - is the number of story branches and optional areas. I noticed after finishing Resident Evil that my ending was assigned a number, and discovered online that as well as multiple endings there were also many scenes and items I hadn’t seen (I knew there was a reason I kept finding shotgun shells…).

Typewriters serve as the game’s save mechanism, and you as the player must find ink ribbon, which is consumed each time you save in a safe room. This adds a tactical element - you must plan not only for your next fight, but also the journey there - but it can make it costly to work out the slightly clunky controls early on when dying sets you back so far, and if you use too much ribbon too quickly then you can end up essentially being held hostage by the game, forced to play on until you find more or lose your progress.

My only other gripe is that Resident Evil can be quite fussy with the angle at which you approach items to interact with them. You must be very precise, or Jill just won’t pick objects up. In one particularly bad example this fussiness led me to believe I couldn’t collect the grenade launcher, and I fought a challenging boss fight without it before later realising my mistake.

Holding strong

I’ve called out Resident Evil for some of its residual jank through this article, but I don’t want to give the impression that I didn’t enjoy it. The story, the mechanics, and the general atmosphere together make it something special, and while the HD remaster has had quite a facelift, it’s amazing that the core of the game - still present in this version - holds up so well after 26 years.

Modern video games tend to hold your hand so much that gameplay becomes a case of a following a list of instructions on the HUD. Resident Evil was a refreshing departure into a time in video game history where the player was provided with very little guidance. It requires you to keep mental notes and act on your hunches, and is more rewarding as a result.

Throw in the detail in the notes and diaries, and all the background mathematics that randomise various elements of the environment, and you’ve got a game that still stands its ground in 2022. Even if, like me, you never played the 1996 version or the GameCube upgrade, I’d urge you to give Resident Evil HD Remaster a go. If you can look past a few rough edges in the camera and combat, it’s a great refinement of a classic.