Concord's failure should be a wake-up call for the video game industry

What a week it’s been in the video game industry! We’ve witnessed one of the most remarkable failures ever, as Concord - the Firewalk Studios-developed live service game into which Sony had invested so much in the hope it would be the next big thing - was shut down after just two weeks in operation.

Much of the criticism of the title was written off by its supporters and the press as “hate”, but this story is actually a culmination of a number of factors that should not be swept under the carpet. If they are, then game developers and publishers might miss the important lessons that should be learnt from Concord’s demise.

What happened?

Sony’s new live service hero shooter Concord was released on 23rd August. With a newly-acquired studio, eight years in development, and a reported budget upwards of $100 million, it’s fair to say that the PlayStation maker had a lot of eggs in this basket as a cornerstone of its new live service strategy.

It lasted just two weeks. On 3rd September, Sony announced it would shut Concord down and refund anybody who had bought it. Apparently, only 25,000 units were sold. It was perhaps the most disastrous launch in video game history.

As the news broke, online discourse showed its usual lack of nuance. Mainstream gaming sites mostly took the stance that this was a negative outcome. Concord was built by a hardworking team of developers, they said, and it was insensitive to dance so gleefully on the grave of their failed project.

But while some commenters undoubtedly overstepped the mark, Concord’s death was lapped up not because players despised this particular product - most were simply indifferent to it. Rather, both the game itself and the discussion surrounding it were symptoms of wider issues in the industry, and blanket labelling critics as haters is a sure way to learn nothing from its failure.

Why did Concord fail?

To learn from Concord’s collapse, we first need to examine the reasons for its demise - and there were several. The game’s development, marketing, and release were a perfect storm of misguided ambitions and outright mistakes.

1. Concord was a £35 game in a free-to-play market

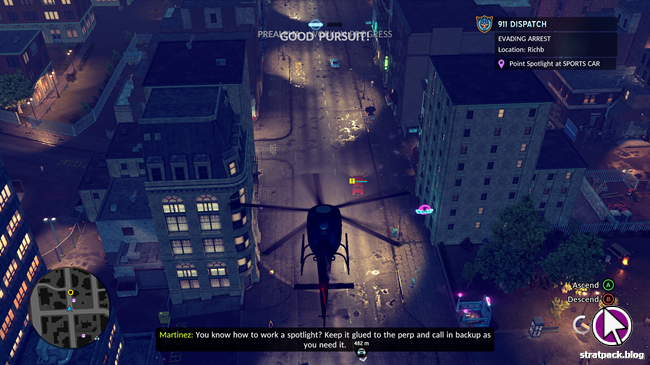

Concord was a multiplayer hero shooter, butting heads with the likes of Overwatch and Apex Legends. These games share two characteristics: Firstly, they have established player bases; and secondly, they’re free to play.

Your average 13 year-old (and let’s be honest, kids are the primary market for this type of inoffensive, colourful shooter) is going to come home from school and log on to whatever their friends are playing. This is likely to be the most accessible title - something the whole gang can just download and play. Kids don’t have £35 to risk on a game that might be worthless if nobody else plays it.

2. Concord was a betrayal of players’ trust

With eight years in development, not only did Concord miss the boat on hero shooters - Overwatch was released in 2016 - but the genre itself was the antithesis of everything Sony and PlayStation had built their reputation on.

When Microsoft went wayward by focusing on the Xbox One’s media features, Sony went all-in on games for the PlayStation 4, even using the tagline “for the players” to launch the generation. It earned trust with high-quality single player games like Bloodborne, The Last of Us, God of War, and Horizon Zero Dawn.

Some live service games have certainly achieved great success, and no doubt somebody at Sony has their eye on Fortnite’s revenue figures. But they’re not what Sony has become known for, and the players who spent £500 on a PlayStation 5 did so because they expected more very polished single player releases - something that has been sorely lacking so far this generation.

3. Concord felt generic and corporate

The first significant glimpse of Concord that I saw was a cinematic trailer shown during a PlayStation State of Play in May 2024. The clip was a little less than five minutes long and told a story where some of the game’s main characters worked together on a mission to track down and extract some sort of artefact. Initially, my main takeaway was that the CGI graphics looked fantastic.

Then they opened their mouths, and that impression immediately changed. Nearly every time a character spoke, it was a cocky, sarcastic one-liner that attempted to prove that they knew best. Coupled with their designs, it was obvious that somebody had realised that Guardians of the Galaxy was quite popular and that the path to success was in dialling the obnoxious Marvel-style humour up to eleven. As a result, Concord’s dialogue bordered on intolerable.

4. Concord’s marketing felt like a bait and switch

Any remaining goodwill for the game was damaged by the way it was promoted. While the characters in the aforementioned State of Play trailer did irritate me, that’s all subjective, and I was still hopeful that Concord might be worth playing. It looked like it could be a space RPG offering a more playful alternative to Starfield - not a day one purchase, but still something to take note of.

Evidently, that wasn’t to be the case. After showing the ragtag team working together on a job, the cinematic trailer ended, and we suddenly jumped to… that same team shooting each other to pieces in multiplayer FPS gameplay. It was jarring, and I wasn’t alone in that reaction. Comment sections at the time were flooded with fans disappointed at what it turned out Concord really was.

What can we learn from Concord’s failure?

That covers the main reasons Concord bombed, and there are some obvious tweaks that could have softened its landing at least a little. But what should we take away from this story in terms of the big picture and the future of gaming? After all, if we don’t learn from history, we are doomed to repeat it.

1. The customer is always right

Well, almost always. I’m not saying that studios should be taking every individual tweet to heart (there are some deranged takes out there), but when the reaction to your game reveal is almost universally negative, it’s a good sign that there’s trouble ahead and it might be worth listening up. That said, perhaps those warnings simply came too late in Concord’s eight-year development cycle for the developers at Firewalk to make any significant changes before release.

The real issue for me here is that the project’s very conception was likely focused on revenue rather than quality or creativity. There are probably developers who put their hearts and souls into Concord and I feel bad for them, but a live service game with Guardians of the Galaxy rip-off characters just screams “design by committee” and “shareholder value”. It’s a shame that $100 million didn’t fund four other projects led by directors with unique creative visions.

2. Development cycles are too long

Eight years is an awfully long time. It’s certainly enough time for trends and consumer preferences to change, or in the case of live service games, for other titles to establish themselves as dominant players in the genre and make it extremely difficult to gain traction with something new. And since your game will receive constant updates anyway, why not release a minimum viable product earlier, and iterate on it post-release while it gathers momentum?

But extended development cycles are an issue for the industry even outside of the live service bubble (I’m looking at you, Bethesda and Rockstar). Taking almost the span of an entire generation to release a single title puts a lot more pressure on that game to perform, and a misstep can spell disaster for a studio. A few polished, high-quality games with a more controlled scope - à la the Xbox 360 era - offers more to players and allows companies to hedge their bets.

3. Creativity is undervalued

A game isn’t something you can assemble by studying trends and calculating the correct balance of existing properties’ characteristics. Overwatch gameplay plus Marvel writing does not equal success, no matter how successful they may be individually. The missing ingredient is a mysterious, creative element that only materialises when somebody is passionate about producing something unique that explores an interesting idea. That’s a more difficult environment to cultivate given the scale of triple-A game development in 2024, but it still holds true.

Metal Gear Solid wasn’t special just because it was a good stealth game - it was made memorable by Hideo Kojima’s exploration of themes like war and passing ideas between generations. The Sims lost its magic in later iterations because the originals emerged from Will Wright’s passion for tinkering with his virtual dollhouse and simulating life itself. And while Fable certainly didn’t live up to all of Peter Molyneux’s promises, it still had an unmistakable ambition and personality that means its world is immediately recognisable even 20 years on.

Despite the mammoth industry developers now find themselves in, creating a game is still fundamentally a creative endeavour. Planning, marketing, and other business-like elements are required supporting functions now that the budgets and projects are bigger, but if the ideas themselves are mandated or reworked by the suits, the final product is likely to be a bland rehash of a current fad.

In summary, I hope the games industry learns from the death of Concord and reverses course. We have never seen such an outright rejection of such an expensive product by gamers, and in my opinion there’s a clear underlying message: Games need soul. If the warnings of this saga are ignored, you’ll probably see a lot more indie games on the pages of this blog in future.